Read Excerpt From Ben Askren's Biography "Funky" - TEST

Read Excerpt From Ben Askren's Biography "Funky" - TEST

Read an excerpt from Ben Askren's biography Funky: My Defiant Path Through the Wild World of Combat Sports" about Askren's college recruitment to Missouri.

Read an excerpt from Ben Askren's recently released autobiography about the two-time Hodge trophy winner and Olympic wrestler's path to wrestling excellence and MMA dominance. Askren's innovative style and brash attitude has made him one of the most polarizing and captivating combat athletes of a generation. Below you can find a chapter of his book "Funky: My Defiant Path Through the Wild World of Combat Sports" about Ben's path to choosing to wrestle for the then unproven Missouri Tiger wrestling program. Askren ultimately would help launch Mizzou into national prominence in wrestling.

You can purchase the book here: Barnes & Noble and Amazon.

CHAPTER THREE

Finding the Funk in Columbia

“Nothing is given to man on earth—struggle is built into the natural of life, and conflict is possible. The hero is the man who lets no obstacle prevent him from pursuing the values he has chosen.”

–Andrew Bernstein

Coach Brian Smith will tell you that he called me before that big Fargo tournament between my junior and senior years, when all the very best high school wrestlers in the country were being recruited and I was feeling completely shut out. All these years later he maintains that he did, but…let’s just say we have differing memories on that. I distinctly recall feeling a sense of rejection before that summer’s tournament, and I was using that as fuel going in. I was pissed off that the phone wasn’t ringing.

In any case, when Coach Smith did call me (to my recollection) right after I took fourth that year in the tournament, I was instantly intrigued. The University of Missouri was not a wrestling powerhouse, but they were a solid program, and they were the first to show real interest. That gave me a positive feeling from the start. Maybe all the first-tier wrestling factories with long, established programs had tuned me out, but Missouri hadn’t. It meant something that Mizzou saw me for what I was and recognized the potential I could bring to the team. In my mind, they were the first college to truly see what the big programs were missing, and that sense of discovery matched up well with my motivation to make everyone who ignored me regret it. So I listened to Coach Smith when he called, and somehow, before I’d begun truly exploring my options, he talked me into coming on an early, unofficial visit that August before my senior year.

Looking back, I think he knew. I think he had a feeling I’d fall in love with Columbia and the program and the vision he had for it, and he wanted to give me a glimpse of it all before I got down to the business of official college visits. He knew that an upstart program might speak to a kid like me who fed off of the snubs and doubled down on his resolve each time he felt slighted. He knew some of the kids already in the program would sell it in ways that would speak to a seventeen-year-old kid ready for his first big adventure.

I went down to Columbia with my mom just before high school started that August, mostly just to get a feel of the town, the people, and the situation. There’s no way to accurately convey the impact that visit had on me, because it was such a youthful awakening at the time. I had a great time. From the moment I arrived I loved everything about Columbia, a quintessential college town tucked away like a secret halfway between Kansas City and St. Louis. It was all by itself out in the middle of nowhere, with trees and a river and a bustling campus. Having grown up about an hour from the University of Wisconsin, the idea of college life in Madison wouldn’t have felt completely removed from home.

Columbia would.

Better yet, I immediately bonded with the guys I met on that initial visit, which did away with any foreign feelings a kid who’d never been away from home might have. Mark Bader, who hosted me that first trip, took me under wing right away and showed me around. Bader made me feel like I belonged from the moment we shook hands. I hung out a lot with team captain Jeremy Spates, an all-American who went on to become the head coach of Southern Illinois, and Kevin Herron, who would become head coach at Seckman High School in St. Louis. They were all way older than me; they’d all be seniors by the time I’d be a freshman. Right away, they felt like mentors, guys who had the knowledge I wanted and the experience I could use and learn from. The fall semester had started at Mizzou, and they took me to some block parties in the neighborhood. It was an amazing time. I felt right at home.

The bond I made with those three guys on the first visit was immediate and lasting, as all three remain good friends to this day. They were also pivotal in helping me decide on coming to Mizzou. They weren’t just these fun guys with noses for good parties, they were also the foundation for Coach Smith’s vision to put Missouri wrestling on the map, to bring the program up to a new standard and compete with the Minnesotas, Iowas, and Oklahoma States—all the dynasties of college wrestling. It mattered to them to get better, to keep the program moving full steam ahead.

I enjoyed myself so much that I couldn’t stop thinking about the possibilities in Columbia upon returning to Wisconsin. During my senior year of high school I took my five official visits, which is what the NCAA allows athletic recruits. I visited Edinboro in Pennsylvania and the University of Northern Iowa in Cedar Falls, both respectable schools with good programs and pretty compelling pitches. The problem was they were small towns, very small towns, and I wasn’t sure I wanted to spend the next five years of my life in either place. I visited Arizona State, which had a good tradition and a strong reputation, but it had an equally strong reputation as a party campus. I wasn’t sold that the guys there were taking wrestling seriously enough.

The other school I visited was, of course, the University of Wisconsin.

Being from the Milwaukee suburb of Hartland, the University of Wisconsin in Madison was the school I was most familiar with. Actually, that’s an understatement. I’d envisioned wrestling at Wisco from a fairly early age, and I became a big fan of Donny Pritzlaff, a two-time NCAA champion. I wanted to represent Wisconsin on the collegiate level just as I had my whole life growing up. I really wanted to be a Badger, and I had assumed throughout high school that the Badgers would want me.

Wrong.

Of all the schools I visited, I was most annoyed with Wisconsin, especially when I found out that Badgers coach Barry Davis had been telling people behind the scenes that I wasn’t very good. For a seventeen-year-old kid just coming into his own who’d never missed a single practice in high school, I took it personally. It felt like sabotage. Having interacted on the message boards, I knew pretty well that adults could act out in surprisingly petty ways, but I wasn’t quite sure what I’d done to warrant such treatment in this case—especially from a coach with that kind of influence. Davis, for reasons I never fully understood, seemed intent on damaging my reputation before I even truly had a chance to build it.

The question I wanted him to answer was: Why? Did I have an arrogance about me? Sure. Did I have a smugness about my ability? No doubt about it. I wanted to be the best. Did I buck convention here and there and do things my way? Of course I did. It’s a coach’s job to see through to the person and to help bring out his greatest potential. My coach in high school, John Mesenbrink, allowed me to be me, which I needed to flourish in my own way. Davis didn’t care for the high school me, and I guess he felt compelled to let it be known. The usual dynamic between a kid and an adult is that the adult is the one who gets to be disappointed in the kid’s behavior.

That wasn’t the case here. I was the one who walked away disappointed.

I wasn’t a bad person, and I sure as hell wasn’t a bad wrestler. Of the five schools I considered, Wisconsin was the only one that felt completely offensive to me, given that I was from the state, just an hour down the road. Wisconsin was in my blood, yet they didn’t bother offering me a scholarship. That was a slap in my face, and I have to say it stung for just a minute. Still, I’ve always been super pragmatic (sometimes to a fault), and my more rational side kept interjecting on behalf of any college that was harvesting doubts about me. After all, I had underperformed in the national tournaments to that point, and I knew it. I hadn’t made the impression that some of the other kids had, and I was sensitive to that, too. I understood—on some reluctant level—why schools might be skeptical.

So I packed it all into my resolve. Wisconsin didn’t want me? Fine. I accepted it and focused my attention on the school that did. I went on my official visit to Missouri and essentially confirmed what I suspected all along; Columbia was the place for me.

I made my commitment in mid-November of my senior year. If I was a blue-chip prospect, that chip would sit mightily on my shoulders as I donned the black and gold. The truth was I knew how good I was, and I knew what was in me to do, so it really bothered me that the big colleges—Iowa, Minnesota, Penn State, Oklahoma State—didn’t recruit me at all. That stayed with me. I knew some of the kids who were heading to those schools, and they weren’t better than me. Even if they were, they wouldn’t be for long. I wasn’t a gifted athlete, but I was driven and I was competitive. A competitor can do tremendous things with a perceived slight. Amazing things. Historic things. And Coach Smith tapped into that.

On my official visit he sold me on the wrestling program and the direction of the team. Mizzou was an up-and-coming program on the cusp of breaking through in a big way. He showed me that, above all else, the Tigers were devoted to winning. That in itself was enough, but what closed the deal for me was how Smith saw me fitting into that plan. He envisioned me as Mizzou’s first national champion. The university had never had a national champion, and so he dangled a carrot out there for me to do something not only personal but historic—to be Mizzou’s Trojan Horse on the national wrestling scene. The program was right there, and I was the one who could help get the Tigers over the hump. That got me fired up, as I truly believed—not just in my heart, but in my head, and in the core of my being—that I could be a collegiate national champion. These motivations were what I was working with. I couldn’t express it to Coach Smith at the time, but I was hell-bent on making his vision come true.

Of course, it didn’t take long for me to come crashing back down to earth. I was redshirted my first year, which I’d expected coming in, and that meant I couldn’t wrestle in the main varsity events. I did get to compete in the open-tournament stuff, and there were some hard lessons to be found there, especially early on. That year, 2003, was rough and at times humiliating. I hadn’t yet filled out physically, which was evident to everyone in the room, a room filled with absolute monsters who worked me over regularly. Future UFC champion Tyron Woodley was there at that time, competing at a weight class lower than mine but already a beast. So was the all-American Scott Barker. You had guys like Kenny Burleson and Jeremy Spates doing their thing, all-Americans who were lifting Mizzou into the national spotlight, squarely on their shoulders. I was learning from, and getting pounded on by, some of the very best in the country. It was a blessing and a curse.

Though I won some matches here and there in the open tournaments, I took a bunch of losses, too. It didn’t just humble me; it left me searching for answers. I’d just achieved the pinnacle of success in high school. I felt invincible heading into college and believed myself ready to take the next step. Now, suddenly, I couldn’t beat anybody.

Or so it felt.

I lost ten matches over a six-week period. Losing ten matches in such a short span was like being sucked into a black hole. I’d lost just eight total matches throughout my entire high school career; hell, I would go on to lose just eight matches the rest of my college career, but I didn’t know that yet. I had hit an early crisis, and, to put it mildly, it was eye-opening. I realized that I wasn’t close to where I wanted to be, and it bothered me in ways I could never have anticipated. That whole season I kept asking myself, is wrestling something I can even do at this level? Is this something I can and should keep pursuing? Is there something I need to change, or do I need to simply accept I’m not that good? All the doubts that come with shattered expectations and failure were flooding me each and every day that I was getting manhandled in practice.

Yet, just like when I’d come up short in that first national tournament in North Dakota, that redshirt year also served as a kind of turning point. I was taking losses because physically I wasn’t in the same ballpark as these guys. When lifting in the weight room, or running “stadiums,” or doing any of the workouts, I couldn’t keep up. I wasn’t nearly as strong or as quick as the high-end collegiate wrestler. Being an awkward kid with the Afro gave me distinction, but not any usable advantages. The losing in the tournaments only compounded all these spiraling developments, leaving me at a breaking point where I kept asking myself the same question, over and over and over: How in the hell do I break this funk?

As it turned out, by discovering it.

I remember telling ESPN a couple of years later in the NCAA national tournament that I developed my unorthodox style out of desperation. That is completely true. I was desperate to compete. After interrogating myself and introducing so many doubts about whether I could succeed at the college level, I came around to my three basic options.

I knew I could dig in, meaning I could just keep doing the same things I’d been doing to get me this far, banking on the hope that—through sheer doggedness of will—things would turn around. I could innovate my style by taking traditional elements of wrestling and adding a spin, some kind of idiosyncrasy to enhance my strengths. Or I could pivot to something completely new. As a work in progress who loved and understood sports psychology relatively well, I was assessing myself by standing back and contemplating the best course of action as rationally as I could.

Of course, I knew what I had to do all along.

I would have to innovate my style. Late into my redshirt season and upon entering my freshman year of competition, I found the funk. What did that mean exactly? I was always conventional in high school, very good in the neutral position, using the take-’em-down-and-let-’em-up method to dominate matches. That wasn’t working in college, so I’d innovate through scrambling. I’d un-inhibit my natural instinct to scramble. I started working with our volunteer assistant coach, Mike Eierman, who’d wrestled at the University of Nebraska and was instrumental in my evolution. Eierman was on the cutting edge in terms of innovation, and the emphasis he put on turning matches from literal physical dictations into something a little more cerebral was tailor-made for me.

Scrambling at this point was very much looked down upon and thought of as junk wrestling, but the more I investigated positions, the more opportunities I realized people were leaving on the table. My ability to exploit these opportunities would become my calling card and help me transform the sport.

I understood I had decent length and could leverage the more prototypical wrestling build, which is generally muscular and squat. My idea was to add entirely new positions to hold opponents in a state of reaction and anticipation, meanwhile putting on a pace that would eventually break them. In other words, I’d use my two best assets—my brains and my motor—against superior athleticism and muscle. I’d make wrestling figure me out, rather than toiling to figure out how to neatly fit into the contours of tradition. This was a game changer for me, a newfound ability to rethink and reinvent. As my redshirt year went on, and I began winning more matches, I started to believe I could match up with anybody. It wouldn’t matter if a Goliath got in my way; I’d make them dance to the out-of-tune music that I alone was making.

Innovating my style really was an act of desperation, but it was also zeroing in on a solution to regain control. If that meant modifying traditional approaches and aesthetics, so be it—the beautiful thing was that there was a method to the madness, and when people caught up to what it was they were watching, it was like the slow dawning of a revolution. Why shouldn’t the improvisational aspects of a scramble become the real story of a wrestling match? It was all leading to the objective of pinning the guy in front of me. To my knowledge, the mad scrambling as an objective had never really been done before. People loved it. People hated it. People were confused and threatened by it. It looked high risk for conventional thinkers, and it was totally different for wrestling traditionalists. It wasn’t artful, but it was relentless and—most importantly—it was me. It was who I was. It was everything inside of me working frantically to turn the tables in my favor, to run in colorful counter to the smooth-rolling norms.

In the simplest terms: I did what I had to do to adapt and, ultimately, conquer.

That redshirt year was perhaps the most important of my college days because it was the impetus for that scrambling, the method that would define me as I went on to rewrite the record books at Mizzou. After that year I qualified for the 2003 World Team trials, which was the highlight of the year because it gave me a real inkling that things were starting to come together.

In my first official match of my college career, I went up against the guy who’d become my collegiate arch nemesis, Chris Pendleton of Oklahoma State. I got up 7–1 in the match by winning a pair of crazy scrambles, which demonstrated for the first time just how effective (and peculiar) the innovations to my game were. I ended up losing the match in overtime, 9–7, but it had been a promising start. Despite the loss, the bigger picture for the program was that Missouri had beat Oklahoma State for the first time in history. Before that, OSU was a dominant 24–0 against Mizzou. It was a seminal moment for the program, and one that Coach Smith would savor as we went forward. There was an anticipation in the air as to how far I could take things in the 174-pound division. It turned out pretty damn far.

I went 32–5 that freshman year and earned all-American honors, while also being named a finalist for the Schalles Award (given to the nation’s best pinner). In the Big Twelve Championships in Ames, Iowa, I ended up going against Pendleton again, whom I’d lost to four times that season and who was cruising to a national title with a 28–0 record. With some familiarity between us, we had a very tough match, only this time I put him on his back with a scramble cradle, which brought the crowd to life. I won the match 9–7 in overtime to take home the championship and was named the Most Outstanding Wrestler at the tournament. It was not only an enormous upset, it was my first major collegiate breakthrough.

I became the first freshman in Mizzou’s history to reach the finals at the NCAAs, which were held just 125 miles down the road in St. Louis. As the sixth seed in the 174-pound bracket, I defeated Pennsylvania’s Matt Herrington and faced Lehigh’s Brad Dillon in the quarterfinal round of what ended up being one of the more memorable matches of my college career. We went back and forth in regulation, and he tied it late to force the one-minute overtime. With the Missouri crowd at the Savvis Center on my side, I won a ridiculous scramble, got a takedown and a three-point nearfall to win 12–7. For a lot of people, it was the first time they’d seen the update in my scrambling style on the mats, making opponents shuffle to the tunelessness of the funky beat.

Though I defeated Tyler Nixt of Iowa in the semis, I came up short against Chris Pendleton in the finals, 11-4. The Tigers were coming up; that much was certain. And the 174-pound weight division knew I had arrived. That year I began to fill out physically. I still had that goal of making the 2008 Olympic team, and everything I was doing was working well toward that goal.

On the international level I was making good progress, too. I did fairly well in the Olympic Team Trials in Indianapolis that year, taking fourth place overall despite being far too small for the 84kg class (185 pounds). I lost to Oklahoma State’s Muhammed “King Mo” Lawal, whom I’d matched up against a year earlier in the university nationals and therefore had a little familiarity with. He was a hulk compared to me, wrestling collegiately at 197 pounds (to my 174), and that size difference played a major factor. I also came up short against the two-time all-American from Cornell, Clint Wattenberg.

What meant more to me at those trials, though, was that I beat the world silver medalist and three-time all-American, Brandon Eggum in the consolation finals. That was huge. I remember I was able to have some decent basic hand-fighting and defense against Eggum, preventing him from getting to any of the stuff he wanted to get to, and eventually I front-headlocked him to score three points. It was the biggest victory of my life.

By my sophomore year I was blossoming into what I’d projected myself to be when I signed on to wrestle at Mizzou, but I came up just short of becoming a national champion. Though I went 34–3, I found myself once again a runner-up for the 174-pound title, losing once again to my nemesis Pendleton in the finals after breezing through Oklahoma’s E. K. Waldhaus and Illinois’s Pete Friedl. It was disappointing. Pendleton just had my number.

One of the strangest stats of my college career was that seven of my eight overall losses came against Pendleton. Though all the matches were relatively competitive, he was the bane of my existence during the first half of my college career, and the monkey wrench to my reaching truly historic heights in college. After all, if Chris Pendleton doesn’t exist, I’m the second-greatest folkstyle wrestler of all time behind only the great Cael Sanderson. Since Pendleton did exist, and he was in the same conference as I was and we found ourselves crossing paths at the same tournaments over and over, there was a force out there driving me every day to get better. For whatever reason, I just couldn’t solve him. Over the course of his career he lost to guys that I would beat, yet math in combat sports is always misleading. The truth is, he was just tough as hell, and I respected him for that. I would lose a match to him, practice where I went wrong, and add a wrinkle for the next match, and he’d come in with a different game plan. Small evolutions. He kept me guessing, and—as rivals do—I like to think I kept him on his toes, too. I was always gunning for him.

Halfway through my time in Columbia, I felt on the verge of something big. The team was on the cusp of becoming a big-time college wrestling program, which was a huge point of pride, and personally I knew I was ready to completely take over my weight class. I was also coming into my own as a person. I was an athlete who definitely had no problem speaking his mind, but I wasn’t going to let regrets become part of my narrative, and I never wanted to be anyone’s redemption story. What I wanted was to be as present as I could in the moment and to dominate, and my life on campus reflected that. The education mattered to me. In retrospect, I wish I’d studied business at Mizzou, but I was a geography major, and I was dutiful in maintaining a good grade point average. I won four Academic All-Big Twelve honors. I liked to have fun, but I didn’t drink, do drugs, or do anything other than work toward my goals of becoming a national champion and making that 2008 Olympic team.

In fact, the only time I willingly took anything throughout five years of college life was when I lost a bet with the heavyweight on the wrestling team, Kevin Herron. We were out playing at the Oakland Disc Golf Course, and he said he would get it closer to the pin than I would, an absurd proposition that I openly laughed at. He bet me, demanding I take a dip of tobacco if he won. Thinking he had no chance in hell, I immediately agreed, then proceeded to hit a tree with my throw. He did not hit a tree. I ended up taking the dip.

I look back at the people I had around me before the start of my junior year and don’t think I could’ve been surrounded by a better cast. I lived off-campus with my teammates Matt Pell, Amond Prater, and Mark Ellis, all of whom were as dialed in as I was. Coach Smith gave me plenty of rope to do the things I wanted to do, as long as I worked hard in the gym. Like Coach Mesenbrink at Arrowhead High, he encouraged my style as well as my sense of self-expression. In fact, back when I began experimenting with the scrambling, it was Coach Smith who encouraged me to work with our volunteer assistant, Eierman. When he saw that it was working, he encouraged me to teach the other guys the techniques that Eierman had helped me with, because he was all about innovation.

And really, those other guys became the bedrock for my time at Mizzou. It was Bader, Spates, and Woodley who had provided something in my scaffolding that I knew was unshakable. Everyone was such a big part of everyone else’s life. We essentially lived, ate, and fought together for five years straight and, in that time, became very close as not only a team, but as a movement with a shared purpose. I loved going to war with those guys. Tyron became a great friend and remains so to this day. Our lives traveled a succinct enough path where—years later when we were both champions in mixed martial arts—he was coming up to Roufusport in Milwaukee to train, spending as many as six weeks in town each time through. Other than his forays into the worlds of acting and rap music, our paths have run pretty parallel.

That whole team was special, including my good friend Matt Pell. We got recruited together out of Wisconsin and were roommates for three years during my time in Columbia. Pell was one of the marvels on the team. After moving up three weight classes, he ended up taking third his senior year and was a big reason Mizzou took third in the country. The younger guys coming in were also buying into what we’d been doing. Raymond Jordan and future Bellator champion Michael Chandler came in two years into my time at Mizzou, and they evolved into fantastic wrestlers. I took both under wing and did my best to mentor them. It mattered to me to be a good example to those guys as I entered what would be my biggest year to date.

If there’s a storied part to my college career at Mizzou—the legendary run that people would revisit throughout the next decade as I ventured into MMA—it kicked off during my junior year. I was ranked No. 1 going in, which put a certain kind of pressure on me to deliver. I loved it. I was right at home amidst that pressure. I was already knocking on the door of breaking J. P. Reese’s all-time pin record (set at forty-seven), and I knew I’d accomplish that fairly early on. I’d worked on my penetration and timing on my shots in the offseason and in summer tournaments, as well as my stance and motion techniques—things that I’d reviewed and pounded my head over after dropping that final match in 2005 to Pendleton. The one thing I felt certain about heading into my junior year was this: that Pendleton loss was soon to become a collector’s item.

I was never going to lose again.

I was like a 174-pound demon of curls and cardio on a kill spree. I was apologizing to nobody, and never once was there a thought (or even a distant uneasy feeling) that I would lose all season. At the Cliff Keen Las Vegas Invitational I broke Mizzou’s all-time pin record and then pinned Ohio State’s Charlie Clark to raise my total to fifty. I would go out there and try to lock up a cradle or a hammerlock as tight as I could, then go for the pin as quickly as possible. I kept seeing and hearing the word “dominating” that season, as in “Ben Askren is the most dominating college wrestler in the country.” It suited me, and, really, I led the chorus. I let people know! I set a school record that year with twenty-five pins, en route to my third go-round at the NCAA tournament in Oklahoma City. All-American? Get the hell out of here with that. I was on another level entirely. I plowed through Lehigh’s Travis Frick (TF 19–3) and Hofstra’s Mike Patrovich (TF 21–6) on my way to a third appearance in the NCAA Finals—this time against Northwestern’s undefeated juggernaut, Jake Herbert.

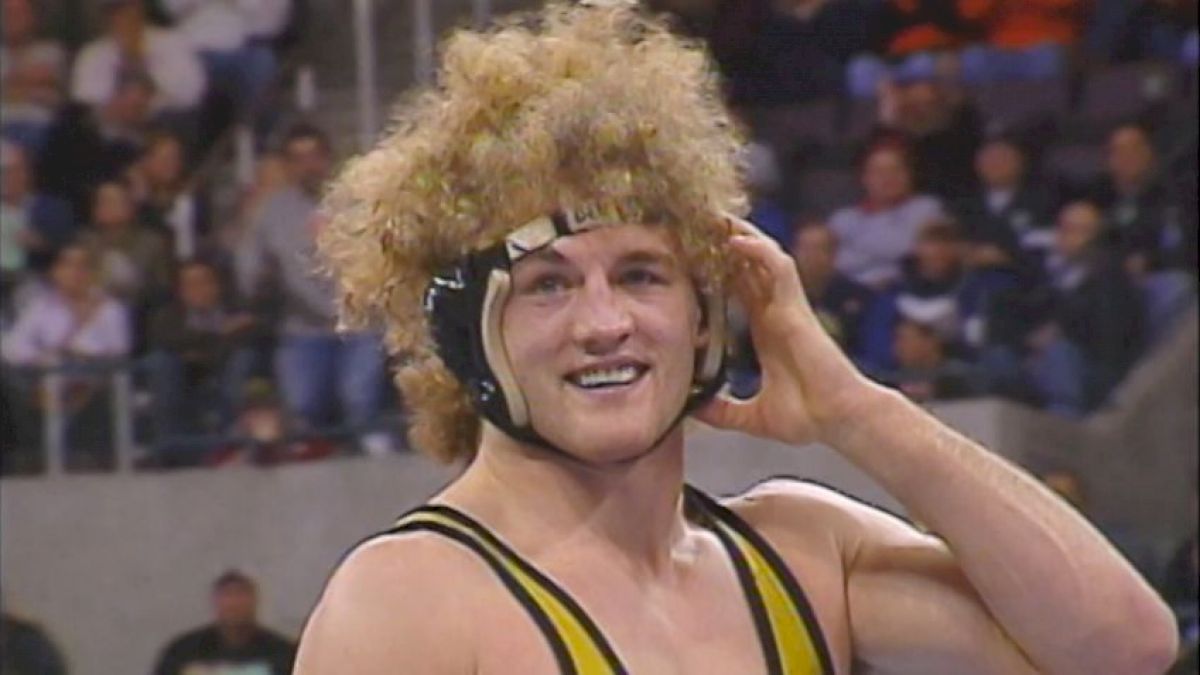

Herbert was undefeated coming into the match and had taken out Iowa’s highly touted Mark Perry in the semifinals to face me in the finals. It aired on ESPN, and the eye test for the uninitiated was comical. Here was a yoked college specimen with muscles forming on top of his muscles, against a gangly, slightly hunching dude with a mashed-up face and an unruly Afro. The building was electric, and I felt invincible as I stepped on the mats. I was in a zone, at the perfect pitch for a competitor. After coming so close to tasting the ultimate glory in folkstyle wrestling the previous two years and working my ass off since the moment I stepped foot in Columbia, I knew it was my time. No psychological barriers could keep me back, no performance anxiety would creep in, and no living thing could keep me from realizing the promise I’d made to Coach Smith when I came in. It was a foregone conclusion that I was about to become a Division I national champion.

I didn’t just beat Herbert; I freaking destroyed him. I picked him apart, winning 14–2. Just like when I’d beat Trevor Spencer in the Wisconsin State Championships six years earlier, I felt like I’d let the rest of the world in on something I’d known all along, through every doubt and every practice and every setback and every run up and down the staircases at Faurot Field. I’d always known I had what it took to be a champion.

Now I literally was one. The endless private toils and hard work had paid off.

It was arguably the hardest route to a national title that year. Everyone knew I was good, but beating the undefeated Herbert, who would go up a weight class the next year and later win a pair of national titles and the Hodge Trophy (handed out to the year’s best wrestler), left no doubt that I was the best college wrestler in the country, no matter the division. It capped off a year in which I went 45–0. I won the Schalles Award for pins, and a few weeks after winning the national title took home the Hodge Trophy, which was the highest achievement of my life. As a kid who fell in love with wrestling in the fifth grade and had dreamed of the Hodge for years—college wrestling’s freaking Heisman Trophy—it was surreal.

It meant just as much to me that Mizzou had its first ever national champion, just like Coach Smith and I had talked about when he recruited me. I’d met a goal, and there were some heavy doses of “I told you so” in meeting that goal, too. For all those big-time wrestling factories that hadn’t recruited me, I couldn’t have been happier to rub it in their faces.

After winning a national title, I also caught a nice glimpse of the other side to a fan’s perspective. In high school, as a stubborn kid who defended himself on the forums and kept winning just to rub their noses in it, I endured quite a bit of antagonism. People didn’t want to see me win back then, and my defiance on that point pissed them off. After winning the national title in college, a strange thing happened: I was almost universally liked, in large part because of the Cinderella element in play. I went to Mizzou, and Mizzou had never had a national champion, which made us the darlings of the dance. America loves underdogs. Storylines are always more meaningful from the unsung perspective of the David figure trying to overthrow a Goliath. I was a breath of fresh air, and everyone was pulling for me and Mizzou to break through.

The “funky” style became a thing after that. With the visibility the event got through ESPN’s national coverage, I did tons of interviews before, during, and after, all centered on the unorthodox approach I took to getting it done. I was the outspoken kid with the curly Afro, the hippie folkstyle wrestler who overcame the guy whose deltoids had multiple definitions (as nouns, verbs, and adjectives)—it was like nothing they’d seen before, and everybody wanted to know more about me. Better yet, I wasn’t a machine like some of these muscle-bound guys; I was more like a cog in the machinery. Years later, FloWrestling did a video feature on me highlighting people’s bewilderment of that match with Herbert, while demonstrating the exotic elements I brought to it. Mimics surfaced almost immediately, and “unorthodox” was suddenly in fashion.

But, as always, wrestling has a way of pulling the rug out from under you. Between my junior and senior years a good deal of those triumphant feelings diminished through a series of unexpected setbacks. I wrestled in the US Open and—to my extreme disappointment—didn’t end up placing. That was a crippling blow to whatever feelings of invincibility I’d built up over the last season. Competition is a cruel and ceaseless master. I was still a little undersized for the 84kg international weight, it was true, but I couldn’t lean on that as an excuse. The main thing was to keep plowing ahead, especially with the World Team Trials coming up a month later.

In late April 2006, while training for those trials, I began to feel some discomfort in my neck—similar to what I had felt in high school when the doctor grimly advised me to quit wrestling. It was gradually getting worse by the day, and it was turning my regular training into daunting undertakings. One day I was doing some warm-up bench presses at 50 percent the weight that I’d normally do, and as I brought the bar down I couldn’t budge it. My spotter helped lift it off me, and I told him to do it again. I brought it down and once again couldn’t budge. I was like, What the hell? I had very little strength in my left arm.

All I wanted to do was put it all to the side and get through the World Trials, but after visiting a doctor I realized there wouldn’t be any World Trials for me that summer. I’d be forced to take some time off, which ended up being a period of just over a month. With where I was in my wrestling career, that felt like five years. It was absolute torture. A young college champion who is ready to showcase on the world stage doesn’t idle easily. He sits and stews and drowns himself in what-ifs. In the end, though, the rest period was probably the best thing for me heading into my senior year. I recovered my strength, and the neck issue—just like back in high school—kind of mysteriously faded away.

I was ready to make some history my senior year, and this time I’d do it with my brother, Max, right there with me. Max, who competed in the 197-pound division, was entering his freshman year at Mizzou as a highly touted prospect. By December we were both ranked No. 1 in the country, which was one of the rare times in NCAA history that a set of brothers topped the rankings simultaneously. Everything was firing on all cylinders, and the whole team was amazing that year. I personally went on a kind of death march through the schedule. Nobody was going to beat me. I had eighteen first-period pins in a row, which set an NCAA record, and finished with twenty-nine pins overall (with twenty-three coming in the first period). I pinned through the Cliff Keen and the Southern Scuffle in-season tournaments and pinned a who’s who of all-Americans. I posted a 42–0 overall record, ending with a match in the NCAA finals against Pittsburgh’s undefeated Keith Gavin. I beat him 8–2 to win a second national title and took home a second Hodge Trophy, becoming only the second collegiate wrestler to achieve that behind only the great Cael Sanderson.

It was during that final tournament the “Funky” nickname that stayed with me through my MMA career truly came into existence. My buddy Marcus Hoehn had come over sometime early that winter with a T-shirt that he’d made, featuring my face under a pile of hair that made me look like a sponge. Above the image was the word FUNKY straight across the chest. I took one look at it and said, “Hey, let’s make a whole bunch of those and sell them at the NCAAs.” I was cunning, see, because you can’t make money as an NCAA athlete…but once it’s over, and you win the whole damn thing, you can do whatever you want. He made about five hundred of them. He and about a dozen buddies wore those T-shirts in the stands during the tournament to advertise them, getting shown on the JumboTron and on ESPN. Everybody wanted one. Right after I beat Gavin to win my second title, I was no longer a college athlete. We walked around the parking lot right in Auburn Hills, Michigan, hawking those shirts. It was brilliant.

The shirt was humorous and it made us some cash, but I didn’t love the nickname. I tried to ditch it when I started my MMA career a couple of years later, but it followed me like a cult from the mats to the cage. “Funky” Ben Askren. Once something like that sticks, you just live with it.

When I look back at my college career at Mizzou, I see it as a night-and-day transformation—the kind of thing I couldn’t have achieved with Coach Davis in Wisconsin or anywhere else. I innovated all the way through my college career, and I couldn’t have done that without the right coaches and team around me. I had to figure out how to thrive rather than just survive, or—worse yet—fail altogether. Things got dark early on, but when I go back and watch myself as a freshman and compare it to what I’d become by my senior year, it’s a world of difference. There are some commonalities interwoven, but it’s two different people. I can see the innovations I fished out of myself, and I can remember everything that happened in between as I tried to get better each time out. People ask me sometimes if there was an epiphanic moment when I realized I’d cracked the code, or figured it out.

The answer is no, not really—not the style, anyway. It was a style, but it wasn’t the style that got it done. I wasn’t out there to prove my style was the best, it was what I had to do to be the best, and I clung to what was working. The puzzle for me was figuring out a way to implement the scrambling, and that meant years of trial and error. I just wanted to win, and the numbers live on in the record books in Columbia. I was 153–8 in college wrestling. I went 87–0 through my junior and senior years, winning two titles and two Hodge Trophies. I finished with 91 falls and 771 dual points. Whether Coach Smith called me before that Fargo tournament to come to Missouri or after, it’s all history—I’m just glad he called. Mizzou wrestling has been rolling along ever since.

After doing everything in my power to leave a mark on college wrestling, there was only one thing left on my mind: make the 2008 Olympic team. That goal, which had been with me the whole way, was all that mattered.